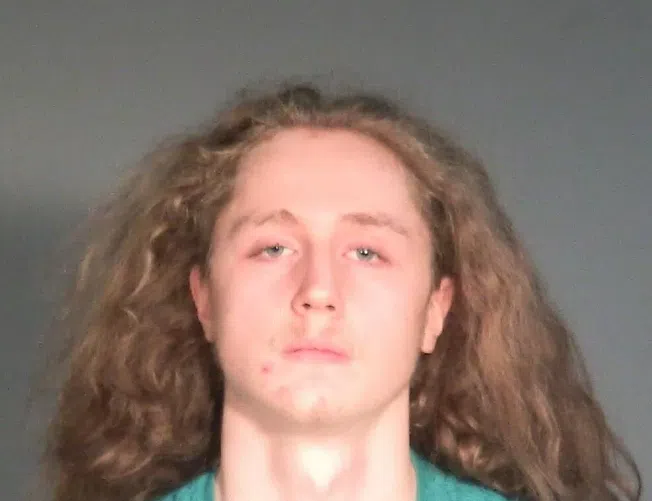

Meillo Schneider (Fond du Lac Co. Jail)

FOND DU LAC, WI (WTAQ-WLUK) — A judge should reject Meillo Schneider’s argument that charges of possession of virtual child pornography violate his First Amendment rights, according to a brief filed by prosecutors.

Meillo Schneider, 21, faces nine counts of possession of child pornography. He has pleaded not guilty. No trial date has been set.

According to the criminal complaint, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children alerted the sheriff’s department about a Taycheedah address where the material was accessed.

“There was over 13,000 files included in the data provided by Amazon.com Inc. Corporation Service Company and Amazon Photos Trust and Safety Team. Det. Tikkanen briefly reviewed the material visually. Det. Tikkanen could see there were thousands of JPG and GIF files of anime/artistic renderings of child sexual abuse material,” the complaint states. “Some of these images were hard to distinguish if they were AI generated or if they were real, unidentified victims.”

Possession of child pornography has been illegal in Wisconsin for decades. Wisconsin lawmakers passed a bill in 2024 which added AI-generated content to child pornography possession laws.

However, defense attorney Timothy Hogan filed a motion, arguing the statute used by prosecutors is unconstitutional, and a violation of Schneider’s First Amendment rights.

He noted the reason why child pornography is illegal: “Child pornography, even if not obscene, may be banned without offending the First Amendment because of the government’s interest in protecting children that are exploited by the production process.”

But, with no actual people involved, Hogan contends the statute is improper.

“Indeed, the Ferber Court recognized that some works of child pornography may have value and that virtual images were an alternative and permissible means of expression. Because the (Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996) prohibited virtual pornography without regard to whether it was obscene, thereby prohibiting materials beyond the categories recognized in Miller and Ferber, it violated the First Amendment,” Hogan argued.

In a 37-page reply filed Tuesday, Assistant District Attorney Kristin Menzl makes several arguments why the court should reject the motion.

The public has an interest in prosecuting all cases involving child pornography:

“By making possession of AI child pornography protected under the First Amendment, it makes the prosecution of child pornography with actual child victims more difficult and, potentially, impossible. As noted previously, AI generated child pornography images have become extremely realistic and tell-tale signs or glitches on an image that used to be indicative of AI generation have been fixed. As such, deciphering whether an image is AI generated or real is no longer as simple as noticing the subject in the image has extra limbs, extra fingers, or is not blinking. Today, AI generated images are regularly believed to be real images and even experts have trouble distinguishing whether an image is real or not,” Menzl wrote.

The expressive interest of the First Amendment does not outweigh the public safety element:

“AI generated images are also making it impossible to solve the child pornography problem by just attacking the possession, production, and distribution of real child pornography. Therefore, the State has a compelling interest in creating Wis. Stat. 948.125 that outweighs an individual’s right to possess AI generated child pornography under the First Amendment. Because the evil to be restricted so overwhelmingly outweighs the expressive interest, if any, in AI child pornography, no case-by-case adjudication should be required and individuals who possess AI generated child pornography should not afforded any protections under the First Amendment,” Menzl argued.

And, because of how the images were stored, the images were not confined to Schneider’s private residence.

“The fact that the defendant’s photos were not simply possessed inside his own home is also highlighted by how law enforcement learned of the defendant’s possession of these images, which was through cyber-tips. In other words, had the defendant merely possessed the images in his home like the defendant in Stanley did, it would not have been possible for a company (Amazon), who had no employees physically in the defendant’s home, to be aware of the images the defendant possessed and be able to forward the information onto NCMEC. Amazon was able to send the tip to NCMEC because, unlike in Stanley, the images in this case were not solely hidden away in the defendant’s home but were uploaded to a storage cloud maintained by a company outside the defendant’s home. As such, this case differs from Stanley because the possession of the images was not solely in the residence of the defendant,” Menzl wrote.

Judge Tricia Walker scheduled a Nov. 10 hearing for arguments in the case. She could issue a decision that day, or craft a written decision to be released at a later date.

Comments